I argue that prioritizing speed over basics in tactical shooting for beginners causes more harm than progress. I am a range instructor with decades of experience teaching civilians and officers the line between good technique and dangerous habit. This article introduces the practical fundamentals every beginner should master before adding speed or complexity. My approach is clinical and practical: I test drills, isolate variables, and reject fads that trade fundamentals for shortcuts. The focus here is on what measurably builds competence — from firearms and range safety to grip, sight alignment, trigger control, movement, and how to practice them through dry‑fire, live‑fire, and simulated training. The goal is an evidence‑informed pathway: who should train, who should teach, what drills work, where to practice, and how often to progress. Expect candid assessments, clear progressions, and objective criteria you can use to know when to add speed and complexity.

Who: Who Should Train and Who Should Teach

Who Should Take Beginner Tactical Training

I screen candidates by intended use, exposure to risk, and baseline skills. Are you preparing for personal defense, occupational duty, or competition? Each objective requires a different emphasis in curriculum and progression. My practical experience, and reviews such as the OJP needs‑assessment, show that aligning content to goals reduces wasted time and prevents inappropriate escalation of skills.

Beginner tactical training should start with an honest assessment of legal mindset, basic marksmanship, and attention to safety. The Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) framework and similar programs underline that tactical training for novices must couple technical skills with legal and ethical context; see the FLETC use‑of‑force training material. In practice, threat recognition, decision‑making, and post‑incident considerations are as important as trigger control — as highlighted in OJP research on officer decision processes (see OJP study).

Limitations are real: some students need extended foundation work, others pursue competition and require different drills. Choosing the right instructor and setting realistic expectations is the core of the “Who” decision. I recommend individualized plans, measurable milestones, and continued practice with periodic reassessment.

Role of Instructors and Training Partners

Instructors and training partners set the tone for safety, learning culture, and long‑term habit formation. A competent instructor should emphasize fundamentals, model restraint and legal awareness, and structure measurable progression rather than theatrics. Training partners should simulate realistic responses while following strict safety protocols so learners receive useful feedback without undue risk.

Good instruction includes documented curriculums, objective performance targets, and after‑action debriefs. Force‑on‑force and scenario work improve decision‑making but must be run by qualified facilitators with medical readiness and clear rules of engagement. Be wary of promises of instant mastery—time, aptitude, and available resources constrain outcomes. Choose teachers who welcome questions, provide documentation of what they teach, and place ethical judgment above flashy demonstrations.

What: Core Fundamentals, Drills and Safety

Core Shooting Fundamentals

The most reliable gains for beginners come from insisting on grip, sight alignment, trigger control, and follow‑through before adding speed. Sight picture and trigger control are inseparable: pairing them deliberately produces accuracy under stress. These elements are motor skills that respond predictably to structured, spaced practice.

My teaching sequence isolates each variable. Typical progressions begin with dry‑fire drills that emphasize grip and trigger press without sighting pressure, then add sight alignment, then live‑fire validation. Dry‑fire drills reduce ammunition cost and accelerate neuromuscular learning, but they do not reproduce recoil, noise, or stress—so supervised live‑fire is essential to validate transitions to dynamic work.

Objective measurement matters. Track group size, split times, and error patterns to diagnose issues and prioritize corrections. Alternatives such as simulators effectively train decision‑making and situational awareness, but they do not replace the motor learning achieved with consistent dry‑ and live‑fire practice. Periodic skills audits and conservative progression reduce risk and reinforce fundamentals over time.

Beginner Drills to Build Skills

Repeatable, measurable, and safe drills form the backbone of early progress. I separate dry‑fire routines and low‑round live‑fire drills, and I treat pistol and rifle work independently so each platform’s ergonomics and recoil management are addressed. Benefits of this approach include rapid neuromuscular encoding, clear performance metrics, and safer range time.

Examples of effective beginner progressions:

– Dry‑fire: draw, presentation, sight focus, and trigger press in 5–10 minute daily sessions.

– Live‑fire validation: low‑round counts (20–50 rounds) emphasizing deliberate aimed fire and slow pairs.

– Movement basics: dry footwork with laser or inert tools, then short live‑fire movement strings with low round counts.

Limitations: dry‑fire can’t simulate recoil or high physiological arousal; live‑fire requires range access and instructor oversight. Prerequisites include basic safety competence, a safe backstop for live fire, and timing devices for measurement. Simulators and coached group classes complement fundamentals but do not replace progressive, measured practice.

Safety Protocols & Range Rules

Safety is non‑negotiable. From negligent discharge cases I’ve reviewed and the course policies I’ve instituted, ignoring a single safety rule can undo years of training. Safety is practical: it preserves lives and enables realistic practice.

Range safety means codified rules and consistent enforcement: muzzle discipline, trigger‑finger control, positive target identification, required eye and ear protection, and the use of snap caps and dummy rounds for dry‑fire and malfunction practice. Instructors must both teach and enforce these protocols and document adherence so training remains credible and legally defensible.

Safety is a continuous skill, not a checkbox. Regular inspection, scenario briefings, and documented after‑action reviews help maintain standards. Facilities, instructor competence, and trainee maturity all influence how effectively protocols are followed.

Where: Best Places to Train

Live-fire Range Training: When and How to Use the Range

Ranges are the place to validate skills under real recoil—not to grind fundamentals that are better rehearsed dry. The RAND review of firearm training requirements and practices supports placing range work after dry‑fire fundamentals have been established (see RAND analysis).

Begin live‑fire with deliberate, low‑round drills: safety checks, slow aimed fire, controlled pairs, and basic reloads, then move to limited movement and target transitions. Keep live‑fire sessions short and focused to reduce fatigue and preserve quality of repetitions. Expect tradeoffs: live fire gives true recoil and sight‑picture confirmation but costs time and money and requires oversight.

Range etiquette is critical: clear verbal commands, muzzle awareness, counting rounds, and proper staging. Use the range for validation and for testing techniques under supervision rather than premature speed development.

Dry-fire Practice at Home and Safe Setups

Dry‑fire is the most under‑used and cost‑effective training tool when done with absolute safety. A disciplined home routine—cleared firearm, target, snap caps for manipulations, timing device or app—multiplies the efficiency of range sessions.

Dry‑fire advantages: high repetition with no ammunition cost, focused motor learning, and quick diagnostics of technique. Limitations: lack of recoil and ballistic feedback, potential complacency if safety rules lapse. Pair consistent dry practice with periodic live‑fire validation to confirm technique under recoil and stress.

Simulated Environments and Force-on-Force Training

When professionally executed, simulations and force‑on‑force training teach decision‑making, stress management, and legal dimensions that static ranges cannot replicate. Research and practitioner experience report measurable value for scenario‑based work in preparing trainees for real‑world encounters (see Force Science summary).

Choose dedicated facilities with experienced referees, medical readiness, and comprehensive legal briefings. These environments bridge the gap between paper drills and practical decision execution but are not substitutes for fundamentals—poorly run scenario training can reinforce bad habits or induce unnecessary stress. Follow strict safety and ethical standards, and ensure beginners have a solid marksmanship base before participating.

When: Scheduling, Progression & Frequency

Training Frequency & Progression for Beginners

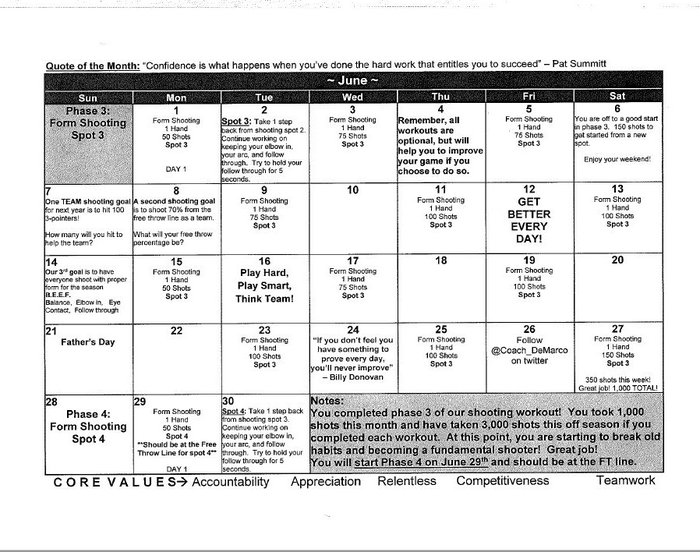

Timing determines retention. Progression without benchmarks is guesswork; I structure stages with objective exit criteria so students and instructors know when to advance. Policy and training literature support moving students from dry‑fire to live‑fire and then to stress drills with documented milestones (see recommended progression frameworks).

My practical recommendation for most beginners: short, focused live‑fire sessions two to three times per week supplemented by daily five‑ to ten‑minute dry‑fire routines. This cadence is aligned with training science that favors spaced practice for motor skill retention (see DTIC review and NIH summaries on spaced vs. massed learning).

Benchmarks for progression include consistent hits at relevant distances under mild time pressure, reliable manipulations, and safe reloads and clearances. Be realistic: limitations such as range access, fatigue, and an overemphasis on speed can stall learning. A balanced plan yields steady gains over months rather than overnight.

Short Sessions vs Deep Practice & Skill Maintenance

Short, frequent practice preserves neural pathways; periodic deep practice days diagnose and correct systemic faults. The cognitive science of motor learning supports spaced, focused repetitions for retention and occasional, concentrated sessions for troubleshooting (see NIH discussion).

Practically: 10–20 minute dry‑fire sessions several times weekly keep mechanics fresh; biweekly or monthly deep days (longer live‑fire sessions or detailed diagnostics) catch and correct persistent errors. Use objective measures (shot timers, group size, consistency under mild stress) to adapt cadence. Avoid rigid schedules that ignore recovery and results.

Little and often keeps skills sharp; occasional deep practice fixes systemic issues that short drills miss. See comparative learning studies for why this balance works (research on distributed practice).

Why: Benefits of Tactical Training and Mindset

Why Fundamentals and Progressive Drills Matter

I teach fundamentals first because in real encounters there is no time to invent technique; progressive drills embed reliable responses under pressure. Stress and decision‑making research used by training institutions supports this sequencing (see FLETC research).

Progressive drills harden motor patterns and give objective performance measures, but they require qualified instruction, realistic stress inoculation, and time. Overemphasis on speed before accuracy typically increases error rates and can create unsafe habits; empirical work in skill acquisition shows quality of repetitions matters more than quantity alone (see motor learning literature).

My approach balances repetition with incremental challenge, data‑driven feedback, and willingness to adapt drills when gains plateau. That creates priorities novices and instructors can follow with confidence.

Why Stress Inoculation and Scenario Work Help

Scenario work converts technical skill into decision‑making under pressure. Properly designed stress inoculation reduces errors and improves performance in real incidents by exposing trainees to realistic cues in a controlled environment. This is supported by law enforcement training literature that emphasizes controlled exposure to stressors with debrief and legal framing (see FLETC research).

However, the benefit depends entirely on execution. Simulations need experienced instructors, strict safety controls, qualified referees, and robust legal briefings. Poorly run scenarios can reinforce bad habits or cause undue trauma. Objectively, scenario training is a bridge between fundamentals and real‑world application when implemented incrementally and evaluated rigorously.

How: Step-by-Step Techniques, Drills & Progressions (Listicle of Practice Items)

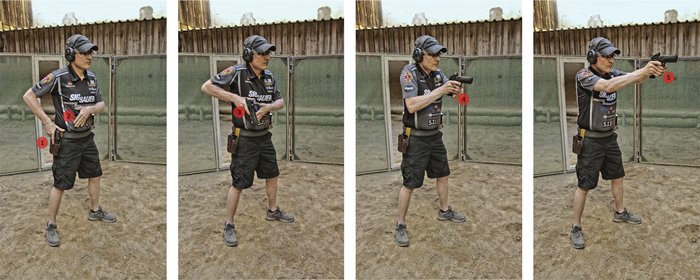

Presentation, Draw Stroke and Holster Work

Safe, efficient presentation is a product of habit and equipment. I teach controlled dry‑fire repetitions emphasizing consistent grip, muzzle control, and a predictable draw path, then validate the sequence with live fire. Research on the startle response and human reaction in draw situations highlights the importance of rehearsed, simple motor patterns (see Force Science summary).

Holster selection is material: retention, cant, ride height, and trigger‑guard coverage affect speed and safety. Duty holster standards and retention guidance can inform choices (NIJ fact sheet; holster study).

Progression: slow, coached dry reps → timed dry reps with feedback → low‑round live‑fire validation → scenario‑paced practice. Limits include comfort, concealment needs, and the fact that dry‑fire alone doesn’t model stress or recoil. Always follow safety protocols and train holster work under instructor supervision.

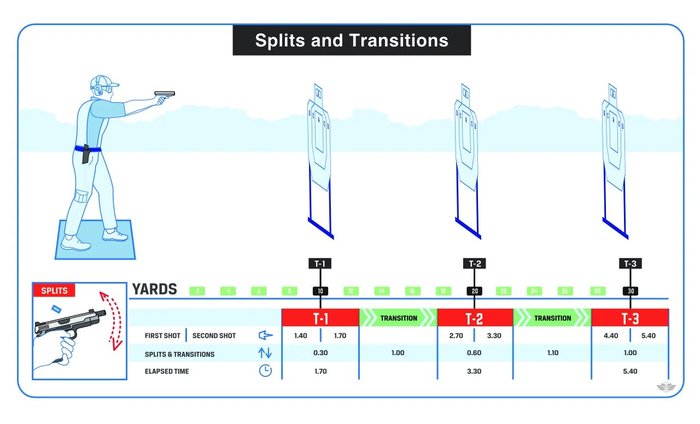

Target Transitions, Speed vs Accuracy and Measuring Splits

Target transitions are measurable skills: how you break contact, re‑acquire, and stabilize affects whether speed gains are meaningful. Timers and group size give objective feedback: split times indicate tempo; group size indicates retained accuracy. Use both to prevent misleading claims of improvement.

Start with baseline single‑target strings and accuracy thresholds, then add a second target and record split times while maintaining group‑size standards. Progressive drills that hold accuracy thresholds while lowering split times produce reliable speed gains. Be mindful that timers can mislead if fundamentals are poor; always pair timing data with accuracy metrics (Speer discussion on split times).

How‑to: record baseline strings, iterate with fixed accuracy criteria, and analyze sessions to identify whether faster splits correlate with acceptable accuracy loss. Use video and timing logs to support objective progress tracking (related performance measurement study).

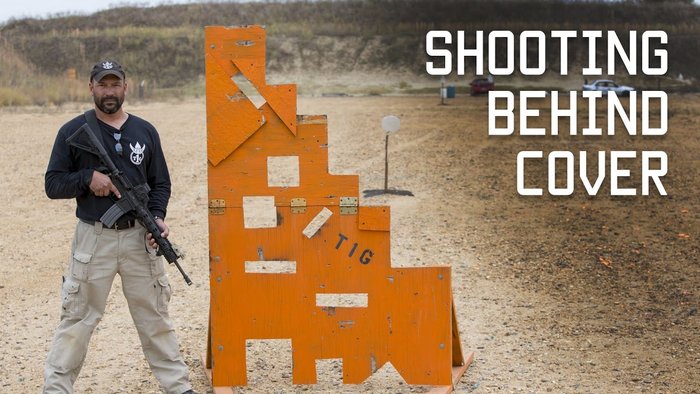

Movement, Use of Cover and CQB Basics

Movement amplifies or degrades accuracy. Teach simple, repeatable footwork and cover usage before advanced maneuvers. Progress dry‑footwork to live‑fire movement: lateral steps, forward‑back spacing, controlled transitions between firing positions, and breath‑timed shots while moving.

Use cover and concealment as tactical options, not guarantees; cover stops bullets, concealment conceals. Explore angles, minimize exposure, and prioritize threat identification and space control before engagement. Practical progression: dry footwork and laser‑based drills, low‑round live‑fire movement strings, then scenario integration with a qualified instructor.

Reloads, Malfunctions and One-Handed Techniques

Practical, repeatable routines for reloads and malfunctions reduce hesitation in high‑pressure moments. I teach the tactical reload, emergency reload, and standardized malfunction clearance sequences with dry practice, then low‑round live‑fire repetitions and timed clearances under light stress.

Layer instruction: demonstration, slow‑motion repetition, incremental speed work, and then application while maintaining hits. One‑handed techniques should be introduced gradually—many students require extended practice to maintain accuracy while manipulating the firearm. Rushed techniques increase the risk of negligent handling; prioritize safe, repeatable procedures.

Low-light, Distance Practice and Advanced Dry-Fire Routines

Because many real‑world encounters occur in imperfect light or at varying distances, include progressive low‑light and distance work. Start with controlled low‑light live‑fire to build sight‑acquisition and target ID under reduced illumination, then add movement and graduated distance increases. Advanced dry‑fire sequences should mimic these conditions safely to train presentation and trigger control in constrained lighting.

Validate dry‑fire sequences with live‑fire or simulation to confirm sighting and recoil control. Equipment choices (weapon lights, optics) and individual sensory limits influence progression. Be candid: low‑light work increases cognitive load and requires careful oversight; start conservatively and document progress.

FAQs

What core fundamentals should beginners focus on?

Which training techniques produced the best improvement for new shooters?

How can beginners practice safely while accelerating skill acquisition?

When is a beginner ready to move from basics to more tactical or dynamic drills?

How often should beginners train?

Frequency and consistency matter more than prolonged, infrequent sessions. For most beginners, 2–3 short live‑fire sessions per week plus daily short dry‑fire practice is effective. Daily prolonged live‑fire is unnecessary and costly; daily short dry‑fire is advantageous if discipline and safety are maintained. Adjust cadence to recovery, logistics, and measured outcomes.

Is dry-fire practice safe and effective?

Dry‑fire is highly effective when absolute safety is observed. Multiple respected sources advocate structured dry‑fire as a primary training modality (SSUSA axioms; practical safety guidance).

Use snap caps and dummy rounds for manipulations, follow strict clearance protocols, and validate technique periodically with live‑fire. Dry‑fire sharpens mechanics and decision‑making at minimal cost, but it cannot replace live‑fire for recoil management and ballistic confirmation (NRA guidance).

What equipment do I need to start?

You do not need top‑tier gear to begin, but you do need reliable essentials: a serviceable handgun or rifle suited to your size and purpose, a sturdy holster appropriate to your carry system, eye and ear protection, snap caps or dummy rounds, and a timing device or app for measurement. Start with serviceable, certified equipment and upgrade purposefully. The California Attorney General firearms safety advice is a practical starting point for legal and safety considerations (see guidance).

Balance durability and ergonomics against cost and legal constraints. If a preferred item is unavailable due to range rules or laws, choose functionally similar alternatives rather than skipping the requirement entirely (range safety rules).

How do I measure improvement?

Measure objectively: group size, split times, transition efficiency, hit consistency under mild stress, and retention over time. Keep logs of drills, video recordings, and timing data to compare baselines to retests. Subjective impressions are unreliable; use simple, repeatable metrics to track real change.

Standardize testing conditions to limit environmental variance and repeat tests periodically to identify trends. When combined with honest instructor feedback, these data inform progression decisions and prevent premature increases in complexity.

Conclusion

Master the basics, train realistically, and never neglect the legal and moral responsibilities that come with skill. Disciplined fundamentals, realistic progression, and ethical judgment create capable, responsible armed citizens and professionals. This article assessed drills, step‑by‑step techniques, and measurable progressions to show why a staged approach matters and how a tactical mindset is developed without rushing. Emphasize core fundamentals, disciplined dry‑fire, and controlled stress inoculation while avoiding common beginner mistakes: chasing speed, neglecting safety, or skipping validation. Use objective benchmarks, honest measurement, and qualified instruction to guide progression. Stay humble, keep learning, and prioritize safety above all.